Many people have been past or on Bank Street. The question that has been asked many times is, “Where did the bank go?” The short answer is that the business relocated to 106 North Main Street, the present location of Allen & Stults Insurance. Anyone who has been in these current offices will see the old walk-in vault that dates from 1875 and the “Bank” sign above it which was from the original bank building from the 1850s, which began as the Central Bank of New Jersey, on the corner of North Main Street and Bank Street next to where the Ely House now stands.

Original vault at 106 North Main Street c. 1875 with the original sign from 1851.

In 1921, when the successor bank sold 106 North Main Street to the Allen & Stults Co., it left behind many boxes of old checks and other items in the eaves of the attic where they had been untouched until yours truly started to dig through them during renovations in the 1980s. One such item was the Board of Director’s Minute Book covering the period from June 1858 through its final meeting on January 10, 1871.

I had copied the minute book and gave same to Richard Hutchinson and the Society about 1998. “Hutch” did some additional research and published an article in three issues of the newsletter, from November 1999 – April 2000. The minute book is not an easy read and some words can be read two different ways due to the penmanship of the time. I had read it a few times back in the 1990s and decided to re-read it due to the recent interest.

The minute book reveals a number of stories that are surprising and intriguing. First, a little history about banking in New Jersey during the 19th century.

New Jersey Banking: A History

Most banking in the 18th and early 19th century was a private enterprise. Member owners of the banks lent to each other or to those vouched for and backed by the owners. Although this was very helpful to the commercial growth of small towns like Hightstown, it did not promote lending to other than these insiders. Borrowing and lending were private transactions on simple pieces of paper. Each state had their own banking laws and regulations and only a couple of federally chartered banks existed and they were located in larger city financial centers (New York and Philadelphia).

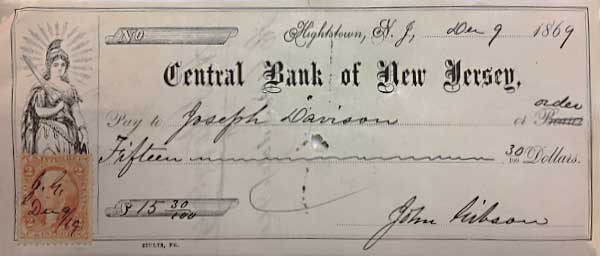

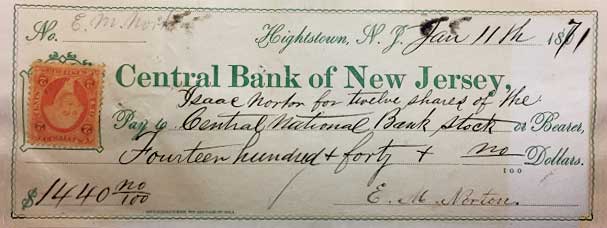

By the 1840s much of banking was through State banks, most of which did not even require a state charter. These local banks actually printed currency, known as bank notes, as well as checks or drafts against deposited accounts. U.S. Internal Revenue stamps were required beginning in 1862 on most if not Original Vault 106 N Main c. 1875 and Original sign from 1851 1869 Central Bank of New Jersey check, with Revenue stamp. all legal documents, including bank checks. The purpose of these stamps was to aid in meeting the costs brought on by the Civil War. As with many government tax programs, the war concluded but the revenue tax stamps continued. (lower left hand corner of check below).

Central Bank of New Jersey check from 1869 with Revenue Stamp.

Central Bank of New Jersey

The Central Bank of New Jersey, Hightstown’s first bank, was formed in 1851 and became a State bank in 1852. Robert Elder Morrison (1800-1873), who had previously been the minister of the Methodist Church in Hightstown from 1843-1845, became President of the bank, and T. Appleget (Applegate?) was Cashier.

By 1858 the Central Bank’s assets were $265,000. Monthly meeting minutes included appointing committees to oversee the “sinking” of the bank notes, which meant a scheduled burning of the Central Bank’s own issued currency, to ensure that the amount in circulation remained limited. The destruction of old, worn-out notes needed to keep pace with the issuance of new ones. The bank’s directors at that time included local leaders and business figures Benjamin Reed, James A. Reed, George Hunt, James D. Robins, Enoch Allen, nurseryman Isaac Pullen, Isaac Norton, Cornelius Wyckoff, mill-owner Redford M. Job and Edward C. Taylor, who was the secretary.

Why Reverend Morrison was named president remains unclear. He was controversial, and Richard Hutchinson characterized him as a “not so reverent Reverend.” My own recent research indicates that the Hightstown Methodist Church records show him as pastor for two years, (1843-1845). He was born in Lancaster, Pa., in 1800, and that he entered the ministry in 1833. As was customary for Methodists ministers in that era, he moved from church to church according to assignments he received from the Methodist conference. Thus he filled the pulpits of Methodist churches in Chester, Pa.; Tuckerton, NJ; Haddonfield, NJ; Swedesboro, NJ; Pemberton, NJ; Long Branch, NJ; Hightstown, NJ; Pennington, NJ; Allentown, NJ; and Crosswicks, NJ. He retired from the ministry in 1847, after his “vocal powers failed” him in 1846. His family history states that his largest salary was $425 per annum. He, Robert Elder Morrison, and his wife Martha Swift, had 6 children between 1827 and 1838. It would be natural for him to seek a higher salary to help support their children. It is not certain what he did between 1847 and when he became president of the bank in 1852, although we know from the Village Record that he entered into a partnership in a store with T. Appleget who had previously been partners with a Norton. Partnership was Appleget & Morrison.

Time to Panic

My records do not tell us anything about the bank between 1851 and 1858. As of this date, I have not found anything in the local papers other than annual meeting notices. But then in 1858, the intrigue begins. Of course, the major event of the year before was the Panic of 1857, which ushered in an economic depression that caused many banks to fail.

August 2, 1858:At the meeting, Mr. Robins offered the following: “Whereas, there has facts that have come to our knowledge since the recent defalcation of some fourty thousand dollars more; and whereas the late president (Morrison), cashier and clerk have conspired to conceal their facts from the directors by covering up their defalcations by false statements there and other misdemeanors committed by them we believe should not go unpunished, Therefore, be is resolved that the president of this institution be directed to bring all these facts before the Grand Jury of Mercer in order that the guilty parties, if guilty, may be brought to justice.” The motion was passed unanimously. (Spelling is verbatim, not this writer’s errors. Note that it says “fourty thousand dollars more.” They clearly knew there were prior losses).

September 6, 1858: At the next meeting the following “preamble” and resolution was prepared and presented to the board: “Whereas, Edward T.R. Applegate through the earnest solicitation of the president and directors of the Central Bank of N.J. has accepted the office of cashier of said institution thereby assuming the responsible duties attached to the same, and whereas through the delinquency of R.E. Morrison , Joseph S. Ely and the former officers of said institution, the assets have in all probability suffered a loss to the amount exceeding one hundred thousand dollars.”

The minutes went on to state that “E.T.R. Applegate is not to be held liable directly or indirectly for any loss or depreciation that have arisen or may hereafter arise in the assets of said corporation against whom a suit is now pending in the Court of Chancery of N.J.”

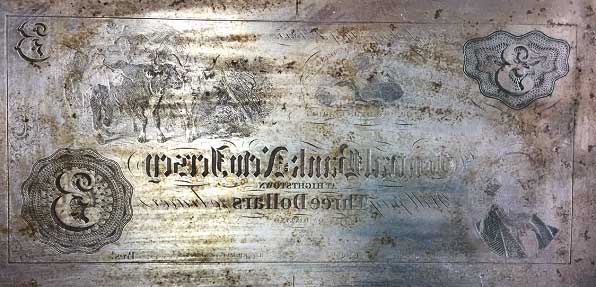

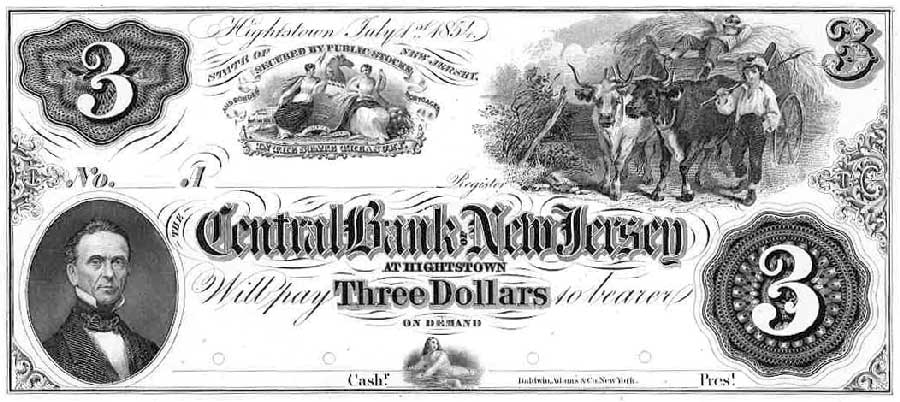

Central Bank of New Jersey $3 note printing plate fround in the A&S attic, and $3 note proof from that plate. Both from July 1854.

As mentioned earlier, banks at this time printed and issued their own currency. The proof copy herein is a $3.00 note. These printed notes could be used almost anywhere that would accept them. Back then, another town’s merchant would deposit it in his bank; that bank may present it to a larger bank, etc., until they would be returned to Hightstown for payment to the last holder. Every month, as indicated in the minutes, the numbered bills were “burned.” A committee of three or more would observe and verify their burning. The minutes state the denomination and number of circulated “bills” that were burned, but not the “No.” on each of the bills. The denominations recorded were $1, $2, $3, $5, $20, $50 and $100s. The banks then of course had blank “sheets” of bills by denomination that had yet to be cut, hand numbered or recorded on the bank records.

Now back to the minute book. In the following month’s entries, usual business was handled including the sale of a Hutchinson property that had been foreclosed as well as the sale of the previously foreclosed “Sloan Mansion”, as it was called in the minute book, to Jonathan E. McChesney for $4,500 (corner of South Main and South streets, currently the Peddie Headmaster’s House and owned for years by the Dawes family).

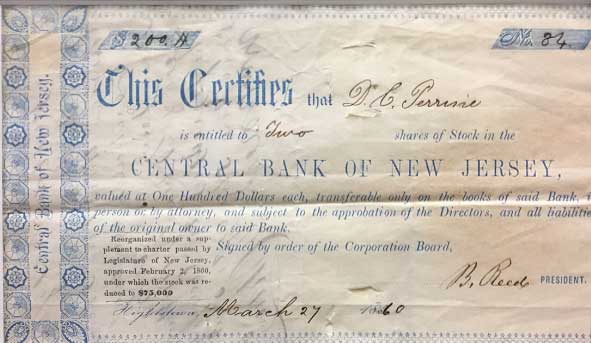

The minute’s next mention of the bank “defalcation” was not until April 4, 1859, wherein the president was directed “to pursue if prosecution of the prior directors was possible.” Months passed with the directors handling the usual business and at the January 1860 reorganization meeting, Benjamin Reed is elected president. E.C Taylor continued as secretary and E.T.R. Applegate as treasurer. The early months of 1860 brought many foreclosures and demands for overdue payments. The local economy would have still been suffering from the depression. The bank’s problems made matters worse. Its assets in March 1860 were only $189,000, well below the figure of a few years before. Stock certificates were being reissued as the bank was being recapitalized at a lower amount. Stockholders at the time were (not including first names) Applegate (3), Allen (2), Bergen (2), Brown, Cubberly, Chamberlin, Cox (4), Crane, Conover, Downs, Dey (2), Day, Ely (4) English, Emley, Early, Forman (3), Fort, Frilder, Giberson, Hunt, Johnston, Jamison (2), Job & Son, Imlay, Keeler, Leane, Lawrence, Meirs, Mount (4), Galliard, Mason, Morrison, Miller, Norton, Pullen (2), Pearce, Perrine(2), Reed(6), Robins (2), Rue (2), Rosel, Slack, Schuyler, Slokes, Snyder, Taylor(2), Vannest, Wyckoff(2), Warwick, Wilson. (the number represents the number of different owners with that surname).

At this reorganization (1860) president Benjamin Reed stated the following: “having now the pleasure of beholding our institution on a permanent basis and in prosperous situation allow me to express the wish that our affairs may never again experience reverses, and that those whose peculations once lightened our cash may receive lodgment in quarters (?) enough to secure indemnity for the past and security for the future. (To save you time searching your dictionary, he said: may those who stole/embezzled from us go to jail).

Original 1860 Central Bank of New Jersey Stock Certificate issued to D.C. Perrine – 2 shares 1860

In the Court documents found by Richard Hutchinson, the bank testimony said that Morrison and Ely were in the habit of taking bills, numbered as well as in sheets, to their own houses for cutting and trimming, nor did they leave a record of the numbers of the bills or amounts. It was also testified that Ely when picking up currency in New York, opened the sealed packages on his own before he returned to the bank in Hightstown.

The bank also alleged that when Ely became Teller he was a man of modest means but became an owner of a lot of real estate and always seemed to have plenty of cash. The testimony seemed to reveal, in Hutchinson’s findings, that Thomas Applegate may not have been aware of these schemes, although his position as cashier, required him to be the overseer of the currency of the bank. He resigned on January 4, 1858, and he told the court that the minutes reflect that the directors praised him for his service (unfortunately our minute book starts in June 1858). Morrison, on the other hand, advised the Court that the blame all was with James M. Cubberly, Teller, who had the “keys” to the bank. Morrison further accused Benjamin Reed and Cubberly as being co-conspirators since 1856. None of this later Court status was reflected in the minute book.

July 1860 – the minutes reflect that the bank pursued collection for significant overdue balances from Joseph S. Ely. The bank has been operating in what they referred to as the “banking house” which was adjacent to the store of J. H. Walters. It appears the bank was renting. In this year they purchased ground from Benjamin Reed and built a bank building. In November Pres Reed was requested to urge on “the Chancery suit.” Also on November 23rd, 1860, the directors voted at a special meeting to authorize the Cashier to “suspend specie payment whenever the extension of suspensions and prevalence of the panic in his opinion demanded such an act.” I assume this was more due to a concern of a national bank “panic” in 1860-1861, rather than the shortages at Central Bank. The “panic” did not happen. Although not stated, this was likely in reaction to Lincoln’s election and fear of southern secession.

May 6, 1861: First directors meeting was held in the “new bank house”, but business was still being carried on in the old quarters. This new “bank house” was on the corner of what is now Bank Street and North Main Street next to the Ely House and what was later sold to the Trinity Church (more on that story here). The writer believes that Bank Street was built at this same time from the grounds of the Reeds.

Business activities moved here on May 9, 1861. In August 1861 the directors approved maximizing any person’s liability (maximum a borrower could be lent) at $10,000 and to attempt to reduce any already higher amount to said $10,000. At the same meeting the secretary was directed to notify the attorneys employed to “bring on the Chancery suit immediately.”

Hutch’s research of the Court record showed no activity between 1858, when the initial filings were made, and May 1, 1866, when Cubberly gave a lengthy deposition to the Court. He was the only one to ever give a deposition.

January 1862 – the directors of the bank advised the “discount committee” (loan committee) to as far as possible give preference to “home loans.” It appears also that during the last year Mr. Benjamin Reed had been behind on loan payments. This had been discussed at a couple of meetings but at this time Mr. Reed offered to give his bank stock as security on $34,000 of his loans, the banking “house” as security for $4,000, and $4,000 in cash. A monthly payment plan was drawn up of 10% of the balance per month until it was paid off. The Bank retained the right to require total payment on a one month notice.

June 1, 1863 – the Cashier was ordered to not allow any person to withdraw his account. There was no mention as to why, but it occurred at a moment when the Civil War was at a low point for the North, and when the finances of the Federal government were very unstable. Mr. Reed was required to bring down loan balances to $50,000 total. The two may be related meaning that the bank also needed cash. We now know from other sources that Benjamin Reed was suffering from poor health.

In 1864 Olmsted H. Reed (son of Benjamin) was elected director to replace Isaac Pullen due to his “non-qualification.” It is not stated whether said non-qualification was due to health or financial matters. During the prior eighteen months or so, many meetings were cancelled due to lack of quorum. President Reed was also absent a number of times. Olmsted Reed resigned as Teller and was replaced by CL Robbins, Clerk and Teller.

October 25, 1864 minutes: “Whereas it has seemed good to the Almighty Dispense of Events to remove from our midst our late worth and esteemed President Benjamin Reed and whereas our respect to his memory render it proper that we should place on record our appreciation of his services, therefore: Resolved That we deplore the loss of our late President softened only by the belief that his spirit is at rest.” Edward C. Taylor was elected President.

It is worth noting that E.C Taylor had served as secretary during the above years. His penmanship was mostly extraordinarily legible. Olmsted Reed’s pen, on the other hand, is not as easily deciphered, nor were others’ who served pro tem as secretary.

In early 1865, there was a disagreement over Cashier Cubberly’s salary. He resigned and was replaced by William C. Norton. Cubberly later changed his mind. It is not clear whether he was given a raise.

March 1866 – the bank had been looking at buying a new building but a turn in the economy and national banking rules caused the directors to put off the new building and to look into “winding down the bank.”

Directors January 1867 were Edward C. Taylor, Isaac Norton, R.M. Job, James D. Hall, Enoch Allen, George Hunt, Olmstead H Reed, Isaac Pullen, James A. Reed. The reasons for Isaac Pullen’s return are unclear, though his tree nursery was an important local business that brought a good deal of outside money into the local economy. In any case, his presence was short-lived, due to his death later in the year. In May 1867, director James A. Reed also died, and Cornelius Wyckoff took his place on the board. As was always fitting, the following resolution was passed: “Whereas we have learned with deep regret of the death of our late associate, James A. Reed. And whereas a due respect for his character as a citizen and member of this organization require that we should pay a tribute of respect to his memory. Therefore, resolved that while bowing in meek submission to this sudden dispensation of divine wisdom we deeply sympathize with the bereaved family in this loss and desire to mingle our tears with theirs to the memory of an honest man.”

Committee was appointed Sept 1868 to determine the status of suit against Morrison and Ely. In October they reported “progress” but on November 2, 1868, the minutes state “President reported that the suit of Central Bank of NJ against Morrison and others has been dismissed for want of prosecutions.”

Directors for 1869 were E.C. Taylor, Isaac Norton, R.M Job, George Hunt, James Hall, Enoch Allen, Olmsted H. Reed, R.S. Mason, J. S. Robbins. This year, 11 years after the foreclosure on Samuel Sloan’s property, the bank wins a judgement in Supreme Court against Sloan and his business partner Andrew Gaddis. Sloan had borrowed from the bank in the form of 7 promissory notes, which he used to finance construction of his house at 230 South Main Street and to keep his dry goods store operating downtown. He had defaulted on these notes. The bank sued him in 1857 and won a judgement against him in Chancery Court in 1858, but he absconded in April 1857, leaving his partner Gaddis behind, holding the bag. With the Panic of 1857 and its resulting depression, Gaddis was unable to make good on these note. This unpaid debt hung over the bank as unfinished business, even a decade later. The minutes in 1869 reveal the bank settled with Gaddis but keeps judgement against Sloan who could not be found.

August 1, 1870 – “on motion it was resolved that the Bank continue on in the same course as formerly and that we show a bold front and do all we can to brake down the influence in reference to starting a new Bank and that the President be directed to ascertain if starting new bank is legal and if not contest it.” This was in response to a new bank that was to open in town in 1870, the First National Bank of Hightstown.

January 2, 1871: At the director’s meeting the board unanimously approved converting from a state bank to a national bank under the National Bank Acts which were enacted to stabilize the national currency and banking due to the debts of the Civil War. It was agreed that all capital would be converted share for share and an additional 280 shares of bank treasury shares were offered. All were purchased by the current owners with the most being purchased by E.C Taylor, William C. Norton and Isaac Norton.

The name of the bank was changed to the Central National Bank of Hightstown. It formally opened its doors as a national bank on January 16, 1871.

E. Norton Check for new shares of the bank after conversion to a National Bank January 11, 1871

There are no further entries regarding the Central Bank of New Jersey so there must be a subsequent minute book of the new Central Bank of New Jersey from this point forward. However the last entry in said 1858 to 1871 minute books is as follows: “Whereas after many years of earnest effort to maintain a reliable banking establishment in this town, dishonorable exertions furthered by misrepresentations of pretended friend has located here an association started to crush us out and erect on our ruins an association of foreign capital, and whereas the directors of the said The Central Bank have used every means in their power to protect our interest; therefore, Resolved That the action of said Directors meets our hearty approval and we hereby tender to them our thanks for all they have done and pledge to them our cooperation and support in all further management of our corporation.”

The aforementioned is not dated or signed but follows the minutes of the January 10, 1871 meeting.

The final item in the records of the Central National Bank is a seven-page indenture dated March 8, 1879. This document records the sale of the Central National Bank of New Jersey’s building and lot to its rival, the First National Bank of Hightstown. It was on this date that the Central National Bank liquidated and consolidated all its assets into the First National Bank of Hightstown.

Much is lacking in my research and there are some conflicts. What happened to Morrison, Applegate and Ely and why was a prosecution not completed? What happened in the years between 1871 and 1879? Was the “foreign capital” of the First National Bank too great for the Central National to compete with? Was the leadership of the Central National Bank too old and tired to compete? The directors were certainly still successful business people and property owners in the town.

Now that the local newspapers from this era are digitized (find that website here), it may be easier to fill in some of these blanks. However, due to the nature of the events, much of the story and intrigue was likely never reported on. The only hope may be some letters to the editor or information in Trenton regarding the various attempted prosecutions. Also the newspaper’s may not have been reporting what was heard on the street.

October 9, 1868: The Court dismissed the case against Morrison and Ely. Thomas Applegate did not appear to have been included in the original action a full 10 years prior to this dismissal. Morrison died of a stroke while vacationing at Ocean Grove in 1872.

In 1879, the Central National Bank of Hightstown, successor to the Central Bank of New Jersey, liquidated and was consolidated into the First National Bank of Hightstown. That bank operated at 106 North Main Street until 1921, when they moved into what is now the Wells Fargo Bank building on the east side of Main Street. Allen & Stults Funeral Directors and Insurance which had been immediately south of the Baptist Church, moved into 106 North Main in 1922, with many of the old bank records in its attic.

Will we ever know the answers to the many questions that remain about Morrison, Ely, Applegate and Cubberly? Maybe they are hidden in the papers I have yet to dust off. Maybe someday soon. If any reader has more information about the above, I would love to have it for the Society. Even if only “leads.” Email us here with any information you find. It will be greatly appreciated.

Support local history like this by becoming a member here.